The performance of white working class children in schools is increasingly becoming a matter of concern. Government ministers and advisers have made outspoken – and often misguided – comments on the subject. The Education Select Committee is currently conducting an inquiry into the underachievement of white working class children. And Ofsted have recently drawn attention to the problem, with Michael Wilshaw stating that schools would lose their outstanding rating if they were found to be neglecting their poorest pupils (including those who are white working class), regardless of the schools overall level of performance.

This focus raises a number of important questions, most of which have not been addressed particularly well by the fragmented coverage of the problem so far. In this series of posts I will consider the evidence for the problem (Part 1), the research into its causes (Part 2) and what the potential solutions might be (Part 3). Turning first to the evidence for underachievement, there are several points worth drawing attention to.

White British pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds perform worse than disadvantaged pupils from any other ethnic group, and the attainment gap is much bigger

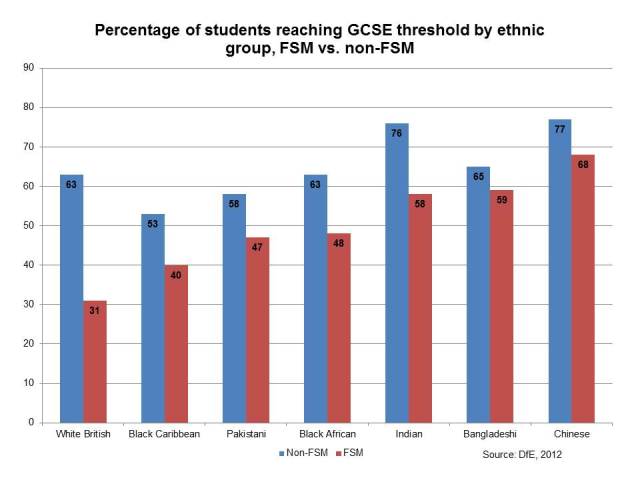

A key piece of evidence for the underachievement of the white working class comes from performance at GCSE. Using the threshold 5 A*-C (including English and Maths) measure, white British pupils on Free School Meals (FSM) do significantly worse than FSM pupils from other ethnic backgrounds, with only 31% of them getting five good GCSE’s.

Moreover, as can be clearly seen from the graph above, the attainment gap between white British pupils is also significantly larger. As Ofsted put it in a report earlier this year:

‘The difference between the attainment of White British pupils from low income backgrounds and their more advantaged peers is much larger than for any of the other main ethnic groups’

The gap is a staggering 31% for white British pupils, with the next largest gap (for Indian pupils) being just 18%.

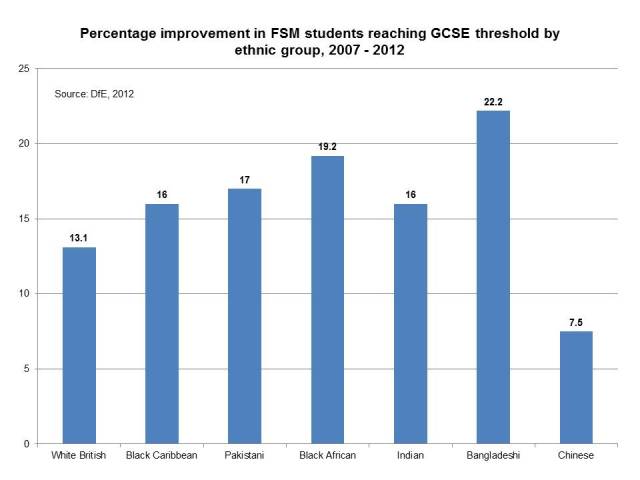

Over the last five years, the GCSE results of disadvantaged pupils from other ethnic groups have improved more than those of disadvantaged white British pupils

Although this underachievement is not a new phenomenon, the evidence does suggest that poor white British pupils have fallen further behind over the last few years. With the exception of Chinese pupils (who were starting from a much higher base), all other ethnic groups have seen a bigger increase in the attainment of their FSM pupils (see graph above). Interestingly, the level of improvement for poor white British pupils (13.1%) is broadly consistent with the overall rate of improvement for white British pupils over the last five years (12.8%).

There does not seem to be a specific problem with white working class boys

One of the key questions is whether gender matters for this problem or not. The Education Select Committee has invited submissions on ‘whether the problem is significantly worse for white working class boys than girls’. A superficial examination of the data reveals that gender does matter – white boys on FSM perform significantly worse than white girls on FSM. There is a gender gap of 9%.

However, this gap is in-line with the gap across other ethnic groups. So whilst white boys eligible for FSM do perform less well, the underachievement of the white working class seems to be distinct from questions of gender. As Ofsted noted, the achievement of white working class girls is equally troubling:

‘While girls outperformed boys across all of the main ethnic groups, the achievement of White British girls eligible for free school meals was below that of low income boys from other ethnic groups, with the exception of Black Caribbean boys.’

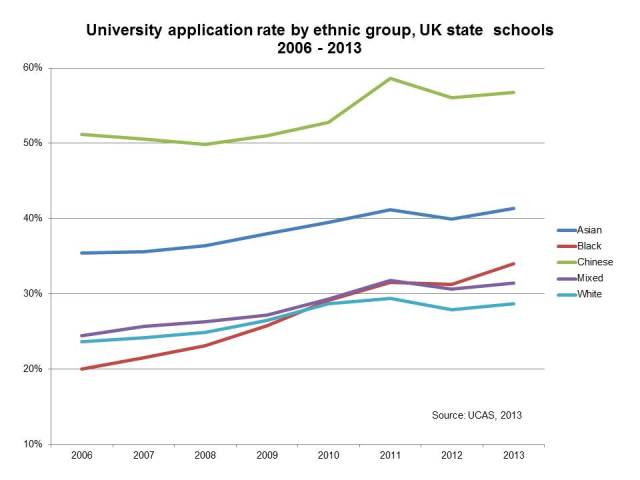

The problem appears to be reflected in university applications

Discussions about underachievement have also included university admissions, particularly after David Willett’s suggested earlier this year that universities should treat white working class boys like an ethnic minority.

Data from UCAS does seemingly support the view that white working class pupils are less likely to apply to university, although this is complicated by the fact that they do not release data on applications by disadvantaged pupils from particular ethnic groups. What the data does show, however, is that white pupils generally are far less likely to apply to university than pupils from other ethnic groups (see graph below). Moreover, the application rate for white pupils has increased less than for other ethnic groups over the last seven years.

Combined with the fact that pupils previously in receipt of FSM are half as likely to apply to university as those never in receipt of FSM it seems reasonable to assume that white working class students are far less likely to apply to university than disadvantaged students from other ethnic groups. Given their underperformance at GCSE this is hardly surprising. Lower university application rates are just another manifestation of the broader problem of underachievement.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Pingback: Educational underachievement of the white working class – Part 2: What do we know about the causes? | British Education Policy

Pingback: Educational underachievement of the white working class – Part 3: What are the solutions? | British Education Policy

Pingback: Would that it be True That All Men and Women are Born Equal – Then Equality in Education Would be for All | Ace News Services

Pingback: Comfortably segregated: UK creeping towards ‘color-coded society’ | ActivistPoster